Despite attempts by central banks to improve communication, the reality is they continue to communicate in riddles. However, every once and while a central bank reveals its hand and provides a clearer picture of its intent. While those watching the Governor’s latest press conference may not have felt a veil was lifted, in reading the RBA’s Statement of Monetary Policy the real message becomes clear.

The RBA’s narrative has been in flux in recent months, shifting from a view that: (i) rates could equally rise or fall in late 2024; to (ii) a one-off adjustment in interest rates in February; to (iii) the latest iteration that the RBA is now on a journey towards a ‘neutral’ interest rate setting.

It is a central bank truism that if you want financial markets to price future interest rates at a ‘neutral’ setting then you set your inflation forecasts at the mid-point of the target band. Typically, a central bank will pencil in hitting the target inflation on a 12-18-month time horizon and financial markets get the hint that the game has changed. The forecast change flags that the central bank is no longer data dependent month-to-month, they are now setting sail for policy rates to move to a neutral setting.

The RBA this week went a step further and pencilled in underlying inflation at close to the mid-point of the target zone for the whole of the forecast period, starting as soon as mid-2025.

This is about as unsubtle as the RBA gets: interest rates are coming down and are coming down at a steady cadence. The only question now is how far?

One gets the sense that the RBA is pretty happy with how the past 18 months have played out from a policy perspective. The labour market is still robust, inflation has normalised and demand growth has stabilised, albeit at a very disappointing pace.

At the risk of being hypercritical, this is in spite of the RBA overestimating economic growth, overestimating inflation and overestimating wages growth for five quarters in a row.

From mid-2024 we have maintained that the RBA was running a little late in starting this easing cycle. Our forecast inflation view was more benign than the RBA’s and our economic growth view more conservative. But with the passage of time and a series of RBA forecast changes, our view is now broadly the RBA’s base case.

However, our main rationale for arguing for multiple easings was not just economic growth and inflation would likely be lower. It was that the nature of what was driving inflation had changed.

Currently, one quarter of the CPI basket of goods and services is already in deflation and one half of the basket has inflation below the bottom of the 2-3% target band. Normally, when inflation has normalised to this extent several rate cuts would have already been delivered by this stage. Most of the remaining items driving the inflation process can be ascribed to taxes and public sector charges, which are completely impervious to interest rate settings. But being late doesn’t necessarily mean you end up cutting by more. Something else is different in the May RBA forecasting round compared to February.

It is notable that the RBA has done a couple of things differently this month:

1. The RBA is explicitly assuming A LOT goes right for China over the forecast period

The RBA has deviated from its policy of using consensus forecasts and applied its own judgement for major economies. In doing so, it is clear that the RBA has adopted the view that the tariff impact on economic growth will be almost exclusively be borne by the US economy – economic growth was reduced by 50pps in 2025 and 2026 – with very modest adjustments made to China and Australia’s major trading partners.

In effect, the RBA is now highlighting that China is a relative winner from the trade war, at least in the outlook period.

Indeed, the RBA is making some key captain’s calls when framing the outlook for policy. They assume that China’s economic growth remains resilient and that the spillovers from trade uncertainty have small impacts on Australia’s economic demand.

Yet they also assume that US tariffs result in a diversion of discounted traded goods to Australia which reduce Australia’s inflationary pressures.

But it’s worth asking: what if China doesn’t fare as well as the RBA’s base case?

If that is your bias, then the RBA is plainly suggesting that a weaker China growth rate results in bigger negative spillovers into Australia and a wave of disinflation from excess Chinese goods.

In other words, if you think the RBA is too optimistic on China’s forecasts, you should be expecting much deeper rate cuts than those implied by interest rate futures.

2. The RBA has crossed the Rubicon and cut their estimate of ‘neutral’ rates

There has been an active debate among the economic community as to whether Australia’s neutral interest rate assumption should be lower than the RBA had been guiding to.

We have been on the side of arguing that economies with high national savings should have lower real neutral interest rates. Given Australia has high and rising gross national savings (thanks to superannuation) it is reasonable to determine that Australia should have lower real neutral interest rate assumptions than peer countries.

The reality, however, is that it does not. The RBA last referred to the real neutral interest rate in Australia being 1%. This compares to Canada at 0.75% and NZ at 0.50% and Sweden at just 0.25%.

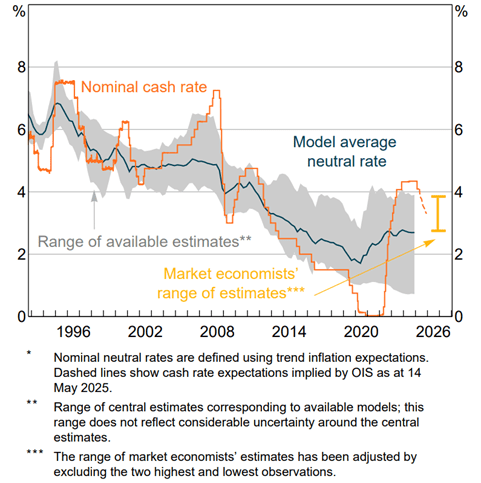

So it was of particular interest that in February 2025 the RBA published a chart of the average of its various model-based estimates of the neutral rate.

It was apparent at the time that the RBA’s internal models were suggesting that the neutral rate was lower than what they were previously guiding to. However, this week the RBA doubled-down by updating the chart and this time added current interest rate futures and market economist forecasts (refer Figure 1).

Figure 1: The RBA’s Nominal Neutral Rate

Source: RBA, February 2025.

This is no accident. The RBA is clearly highlighting that the average real neutral cash rate from its models is as low as 0.25%, some 75bps below its previous guidance. Indeed, neither the low point of interest rate futures nor the most bearish of surveyed economists are forecasting that the RBA will reduce rates anywhere close to this estimate of neutral.

We have been awaiting confirmation that the RBA has lowered its neutral rate, and it is difficult to conclude post the Statement of Monetary Policy that the RBA has not. We have also been awaiting the RBA lowering its underlying inflation forecasts to the mid-point of the target band. This week it has done both!

This is a big deal for asset markets. It suggests first that the journey to neutral has been charted, and secondly that that journey is much further than the RBA had been suggesting previously.

As a consequence, we have added two additional rate cuts in 2026 to our RBA forecasts.

We continue to expect the RBA to reduce interest rates by 25bps in July, August and November of 2025 and now forecast the RBA will also cut rates by 50bps across 2026 (May and August). This would take the nominal cash rate to 2.6%, broadly in line with the RBA’s model-based average of the nominal neutral rate.

0 Comments