Although we disagreed with yesterday’s decision by the RBA to hike interest rates the reasons the RBA cited for the decision are not completely unreasonable. Namely, the RBA believes that:

1. Global economic growth was stronger than expected, albeit their forecast shows that this was only because of stronger-than-expected US economic growth, to whom we have relatively low export exposure;

2. Demand growth in Australia has been stronger than the RBA expected, albeit economic growth has evolved very consistently with our own forecast of private demand-led economic growth; and

3. The RBA’s internal models suggest the labour market is close to neutral and the output gap is positive, suggesting little supply side response in the economy. This is a very different interpretation to our own.

However, we differ from the RBA’s interpretation in five key areas and believe the RBA risks smothering out Australia’s nascent economic recovery just when it was only getting started.

1. The recent surge in the A$ had already more than undone the benefit of the prior three rate cuts

The surge in the Trade Weighted Index (TWI) is arguably far more relevant for monetary policy than any other data point since the RBA’s December meeting, inclusive of recent CPI and employment data. The RBA has gone out of its way over the past year to down weight the role of the ‘cash flow effect’ of monetary policy and upweight the role of the ‘exchange rate effect’ in terms of interpreting the transmission of monetary policy on the real economy.

A strong appreciation in the TWI not only suggests future imported inflation will be lower than the RBA’s forecast, which assumes an unchanged exchange rate forecast assumption, it also lowers the future economic growth profile. The RBA Governor stated in the Q&A that the RBA had in fact forecast the rise in the TWI. This is nonsense.

The RBA’s forecast in November was that the TWI would be currently 61.3, they now have it pencilled in for 64.3. This is a very big miss by the RBA, which has significant implications.

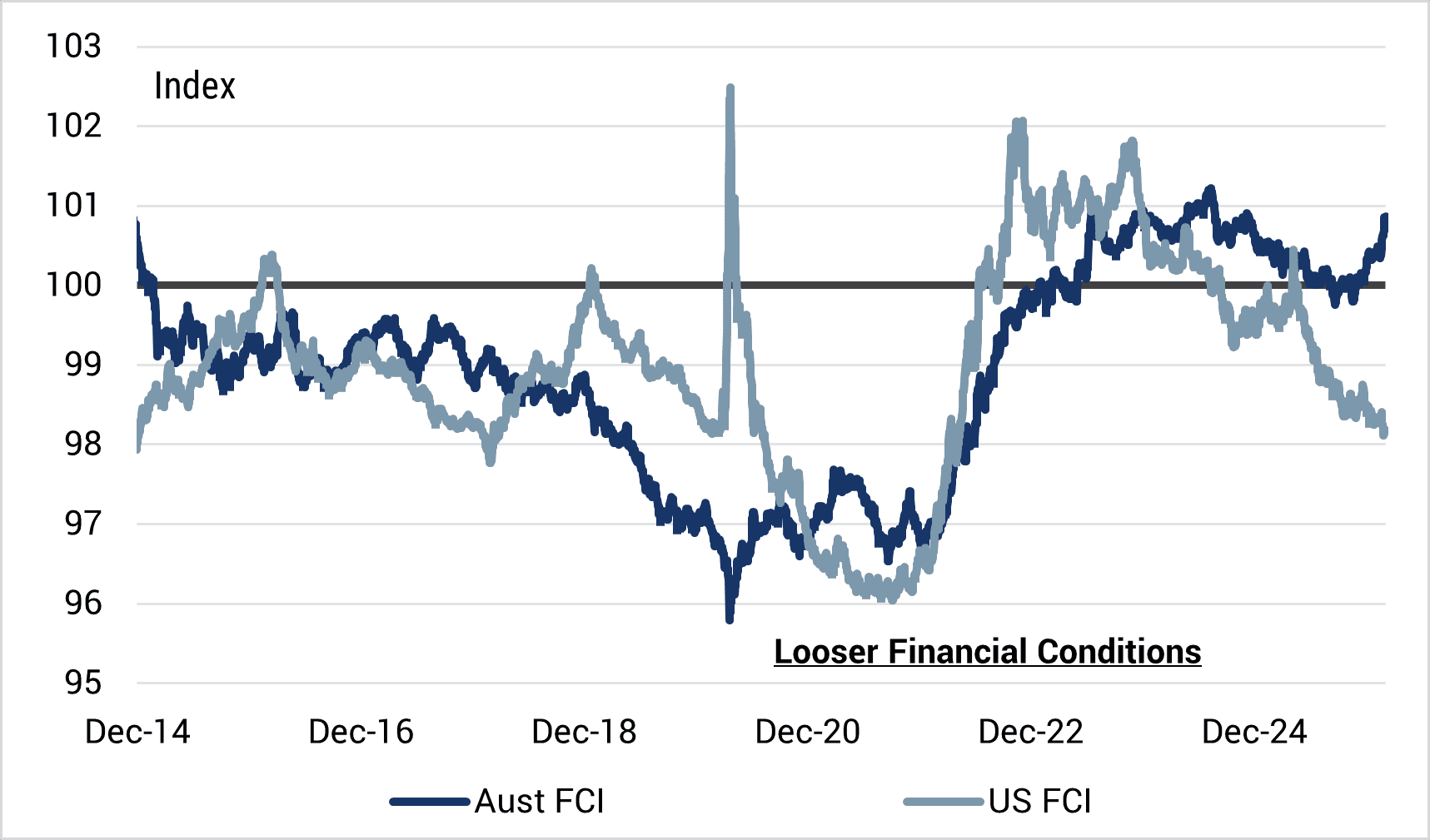

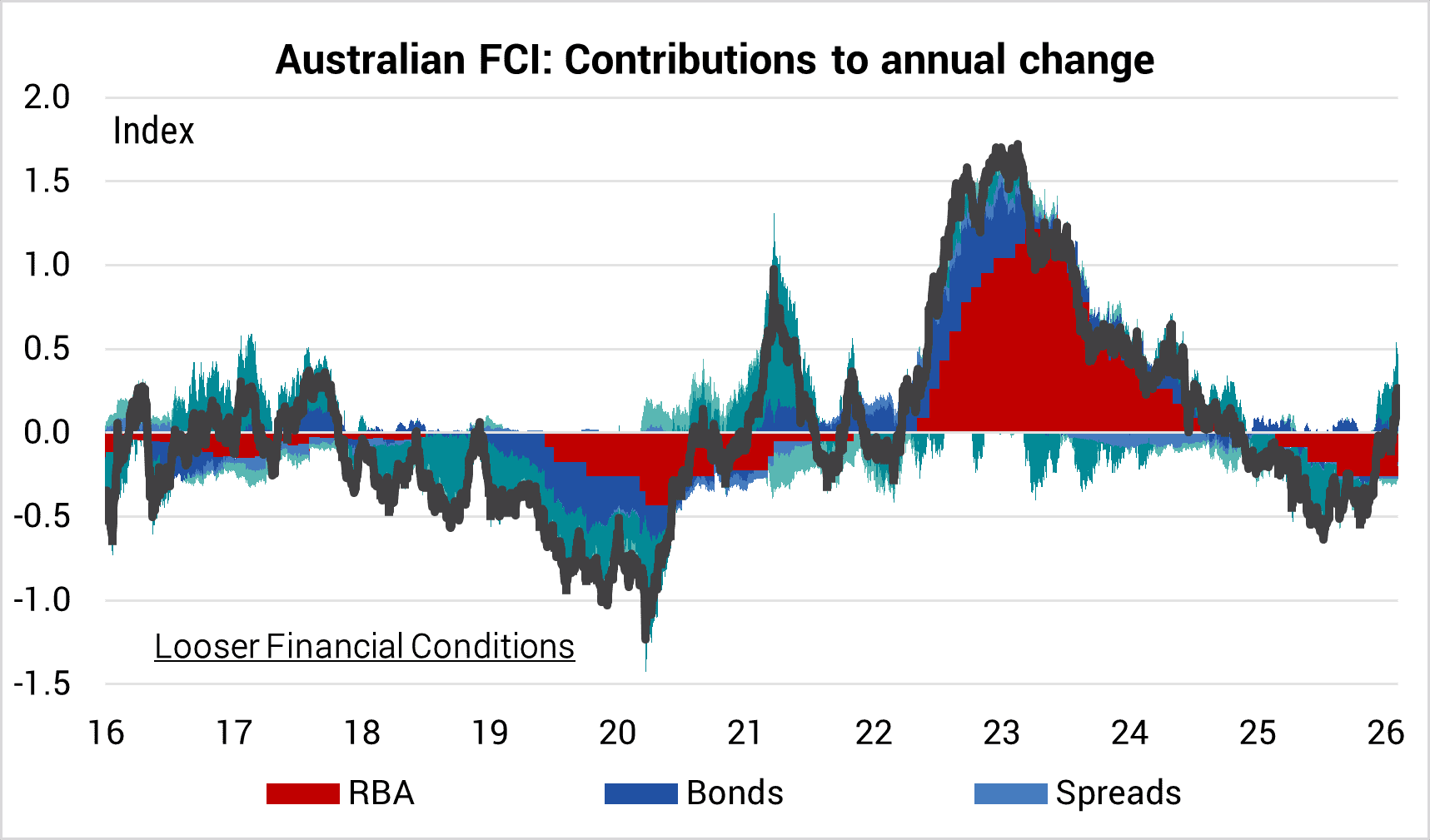

For a central bank that professes to be forward looking, the surge in the TWI has resulted in an unanticipated tightening in Financial Conditions in Australia which brings important implications for future inflation and economic growth. Importantly, this stands in stark contrast to US Financial Conditions which have continued to ease sharply since the RBA’s last meeting.

The RBA now finds itself in a position where the appreciation of the A$ has more than offset the impact of its three interest rate reductions. Relative to mid-2025, when Financial Conditions could reasonably be described as at a ‘neutral setting’ consistent with future economic growth expanding around ‘potential’, Financial Conditions are now clearly back into the restrictive zone.

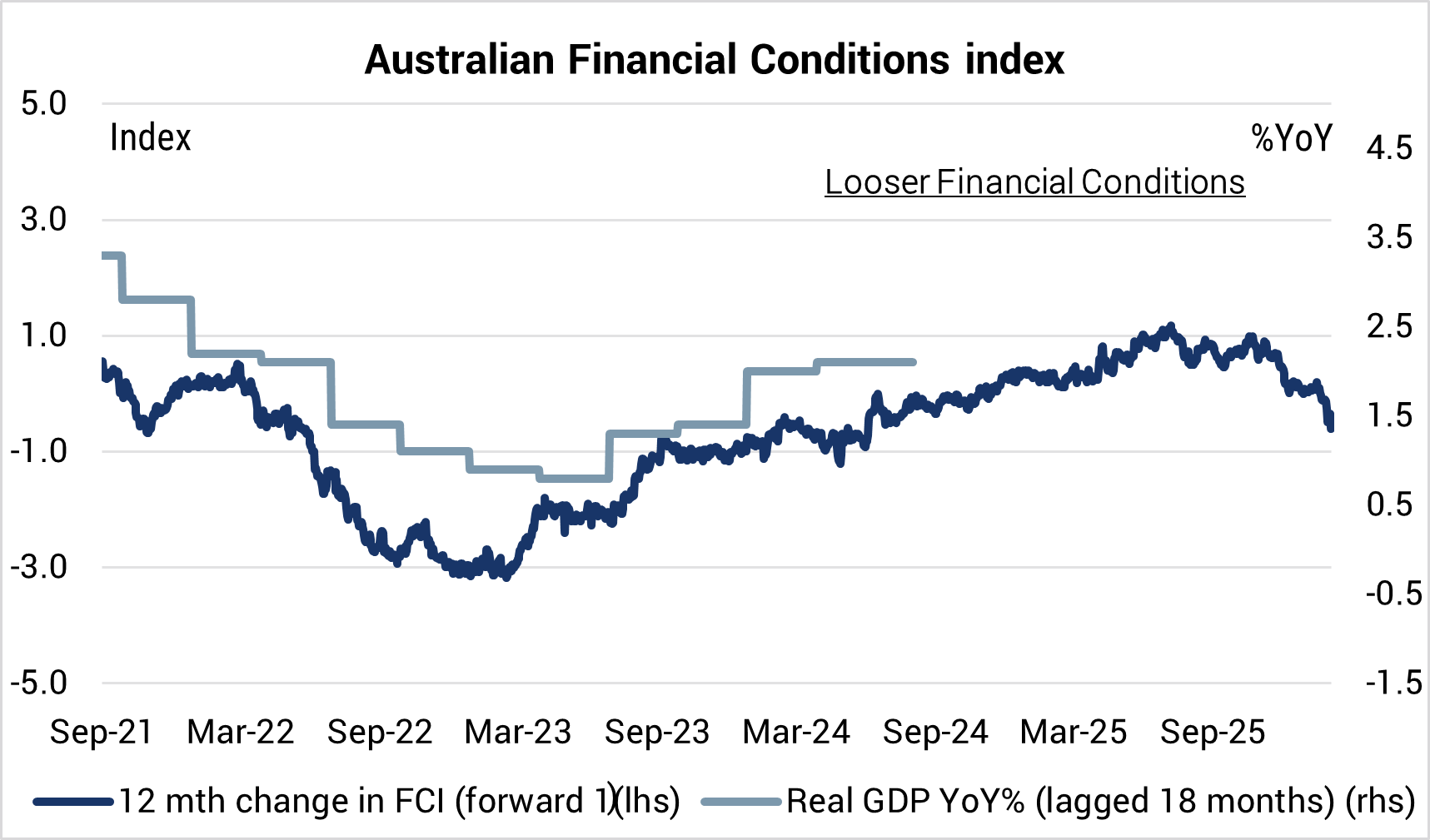

The implication is that economic growth will likely peak into mid-2026 and slow back to a sub-potential pace of below 1.5%, all else equal, and in turn remove any genuine threat to inflation exceeding target on an ongoing basis.

Embarking on a new interest rate hiking cycle at this time only compounds any economic slowdown into 2026-27. A truly forward-looking central bank should take far more signal from this recent Australian dollar led tightening in Financial Conditions than the noise presented in recent CPI data distorted by taxes, subsidies and base effects.

From our perspective the RBA should lean on its famous ‘policy of least regret’ framework. That is, to pause and assess the impact of the recent tightening in Financial Conditions rather than compound the effect with a new round of domestic interest rate tightening.

Chart 1. The gap between US and Australian Financial Conditions is getting extreme

Source: Yarra Capital Management.

Chart 2. The surge in the TWI has now more than offset all of the benefits of the RBA’s three rate cuts

Source: Yarra Capital Management.

Chart 3. Tighter Financial Conditions will weigh on future economic growth and diminish demand side inflation pressures

Source: Yarra Capital Management.

2. Sequential inflation pressures have not been alarming

The RBA has been quite selective in its description of the inflation data. The RBA has chosen to use half year on half year data to illustrate a re-acceleration in inflation. However, the surge in inflation has little to do with sequential inflation pressures post July 2025.

The RBA’s last interest rate cut was in August 2025. Over the period of August-December 2025, the ABS’s seasonally adjusted monthly CPI rose on average 0.26% (mom), a 2.64% annualised rate. By comparison, the CPI averaged 0.33% (mom) from January-July 2025, a 3.94% annualised rate. Given the RBA’s interest rate reductions in February, May and August 2025 only had the January to July data at the time of August’s RBA decision, it is notable that sequential inflation pressures have eased just as the RBA has pivoted to be more hawkish.

There is still much to learn about the seasonal patterns of the new monthly CPI data, but what we can observe is that it is noisy, particularly around calendar year end. To get a sense of the type of volatility in the new monthly CPI data, the ex-volatile (i.e. ex-petrol and fresh food) measure rose 1.0% (mom), but the ex-volatile ex-holiday travel measure of inflation was flat in the December.

There are obviously large price spikes detected in the December monthly data for holiday travel that are clearly impacting the data, and these will reverse back out next month. In short, making firm decisions over whether to embark on a new tightening phase on year-end inflation (and employment) data is fraught.

Moreover, much of the volatility that has emerged in the inflation data is base effects, tax and subsidy effects that should largely be looked through from a policy perspective since they will soon normalise.

3. Most of the ‘one-off’ price shocks are in decline

The RBA was wary of some ‘one-off’ effects impacting the inflation data. The most notable in the data have been the impact of electricity subsidies, gold and silver prices impacting accessories, meat prices and women’s clothing.

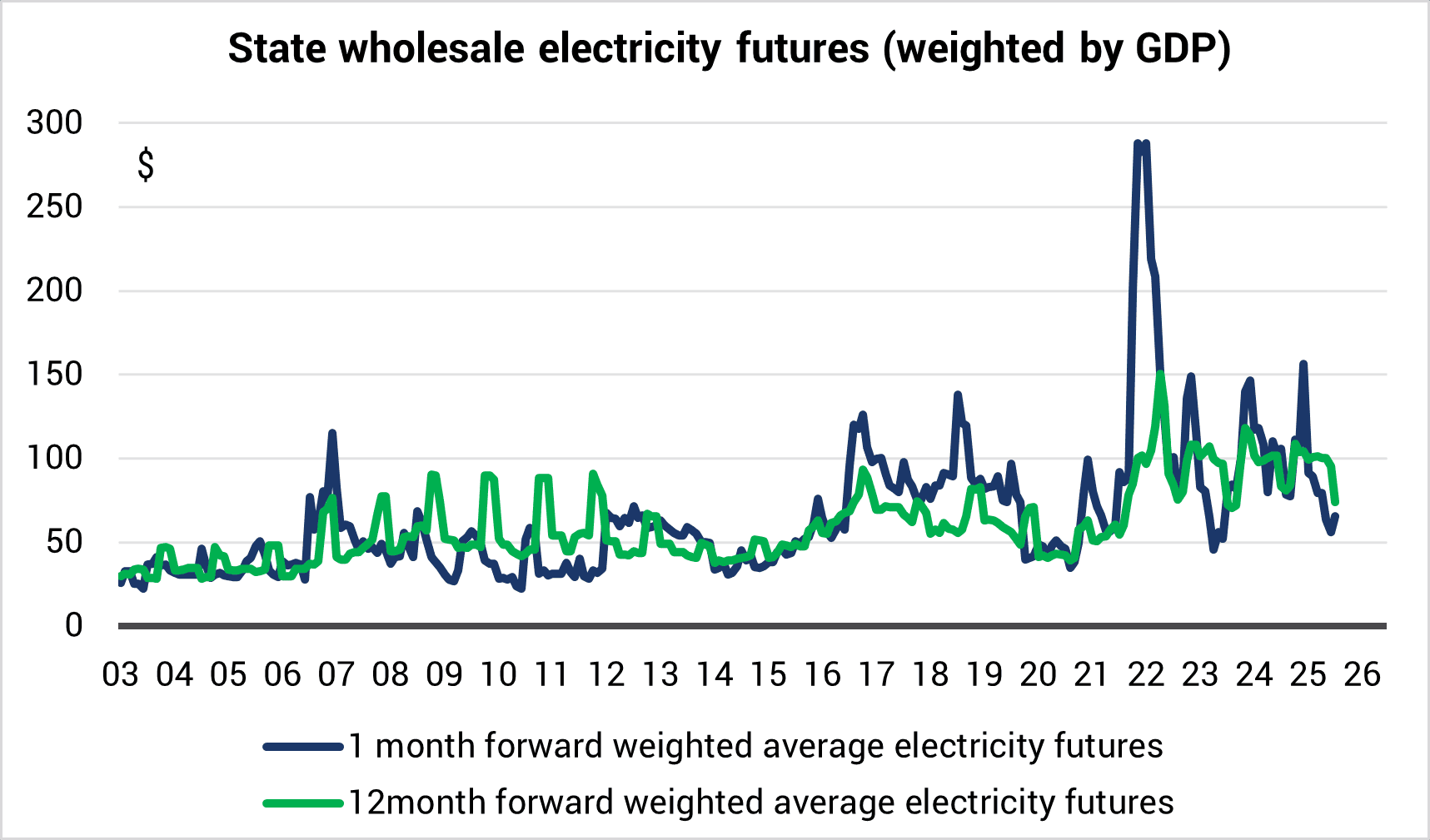

By now, most people are aware that the impact of electricity subsidies paid to electricity retailers rather than households had merely partially shielded households from the real cost of electricity prices which spiked due to both geopolitical and local supply constraints. The decision to no longer extend the National level subsidies has created a sequential re-acceleration in electricity prices as the measured subsidised price converges with the actual price.

However, it is important to recognise that electricity futures finished 2025 materially weaker and are now much closer to long-run average prices. This is good news for retail electricity prices in the upcoming financial year.

Chart 4. The pain of coming off subsidies is mitigated by falling wholesale electricity prices

Source: Yarra Capital Management.

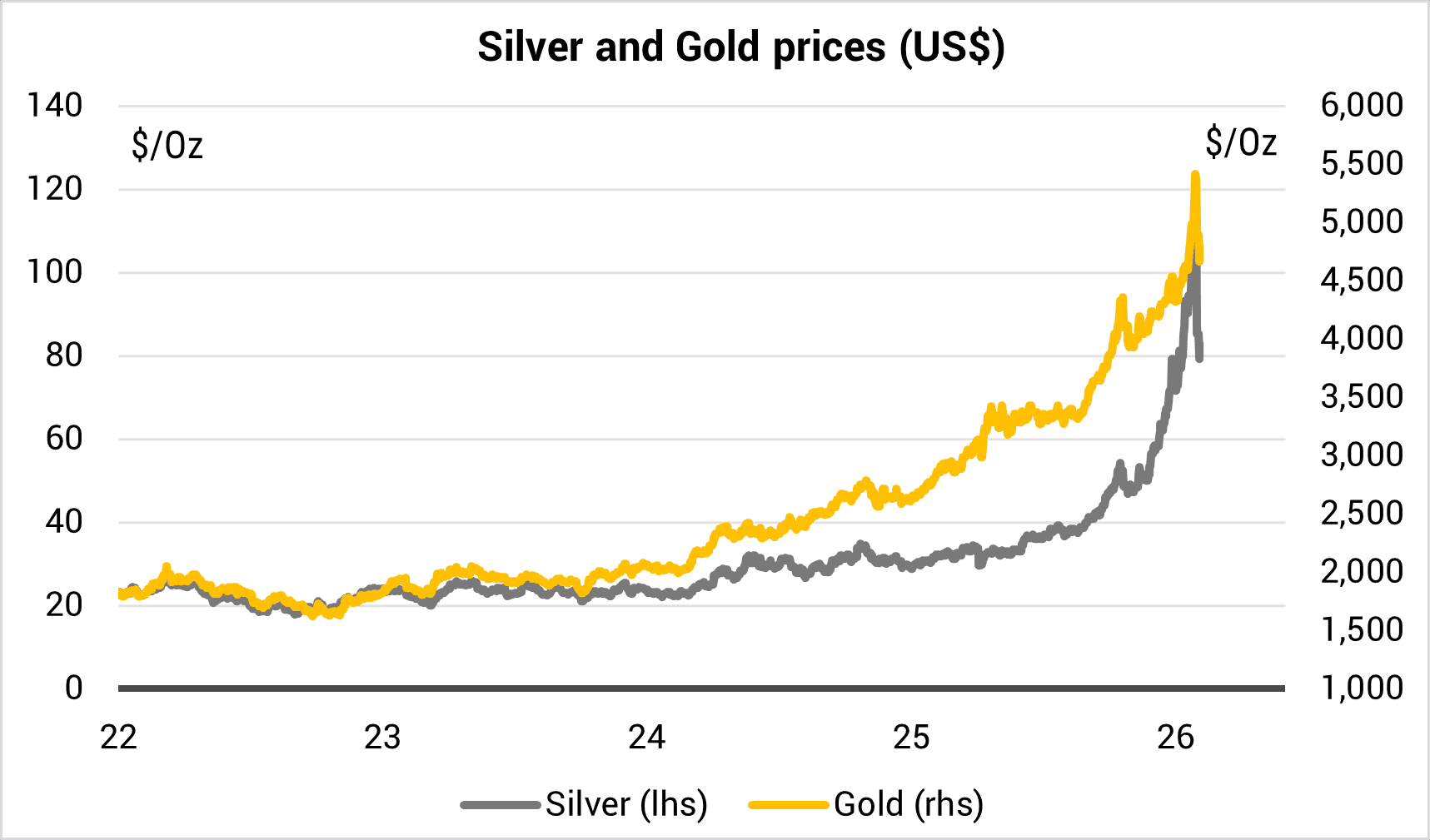

Gold and Silver prices have clearly had record breaking increases over the past year (refer chart 5) and regardless of one’s view of what is bubble-like behaviour vs. genuine structural demand, the price correction in both metals into February provides a reminder that not only can prices fall, but that they would need to continue to rise at the same pace as in the prior year in order to generate the same inflationary effect.

Given central bank purchases of gold have slowed, US inflation has likely peaked and real bond yields have risen it is probably safer to conclude that the inflationary aspect of surging precious metals is more likely to be behind than ahead of us.

Chart 5. Silver and Gold prices provided an unusual but likely one-off inflation impact

Source: ABS, Yarra Capital Management.

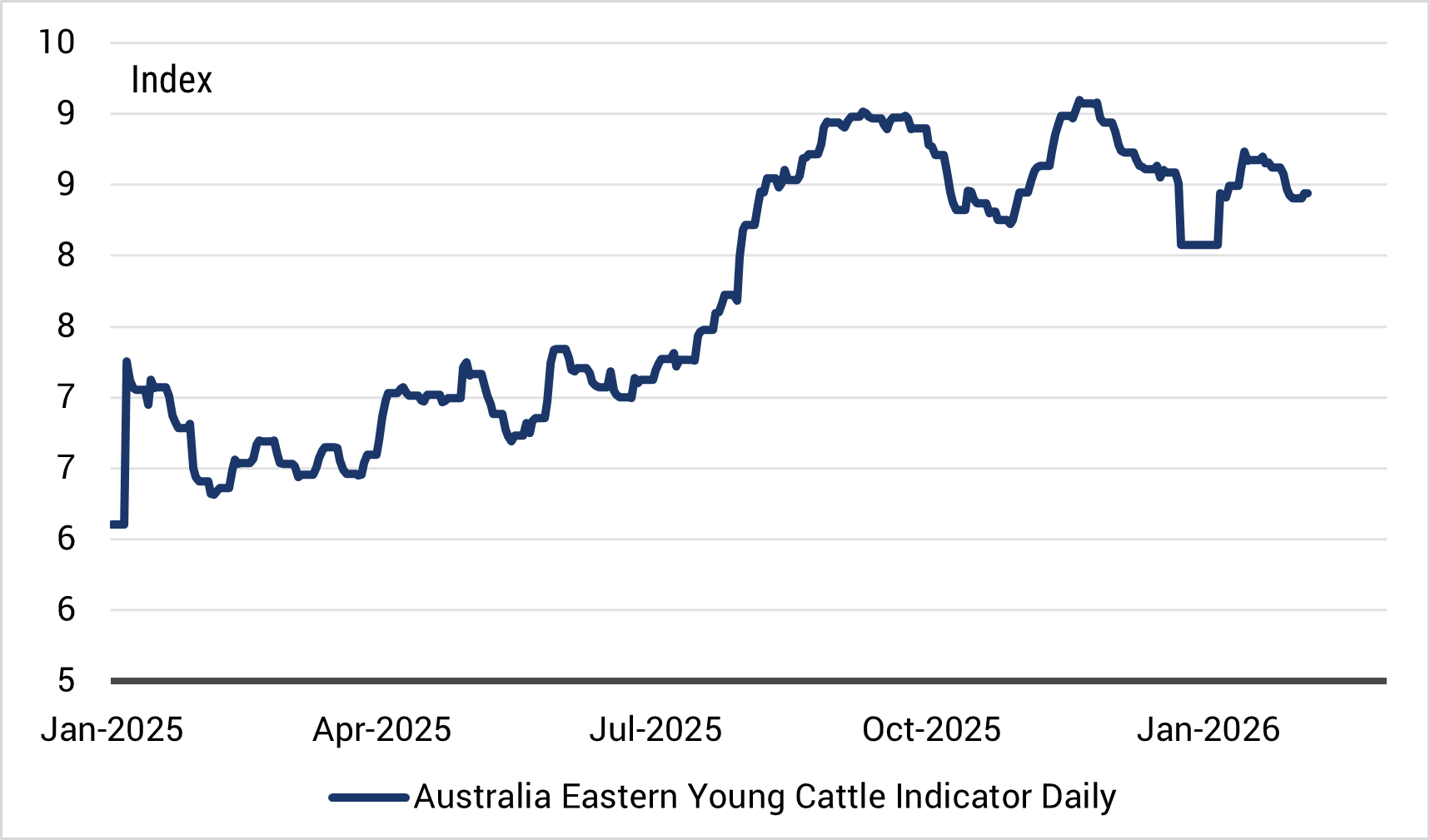

In terms of meat prices (refer chart 6), it is notable that the sharp rise in the daily price of beef recorded into mid-2025 has since faded, suggesting that the annual rate of meat inflation will moderate into mid-2026.

Clothing and Footwear prices are also showing signs of moderating sequentially into the end of 2025 after what appears to be some dissipation of the residual impacts resulting from the implementation of US tariffs on Asian suppliers.

Chart 6. Meat prices peaked towards the middle of 2025

Source: Yarra Capital Management.

4. Inflation expectations are anchored

Typically, the strongest reason to embark on a new hiking cycle is to contain the threat of rising inflation expectations. The only place that seems to have recorded a material upswing in inflation expectations is at the RBA.

Financial markets certainly do not appear to share the RBA’s concern. Ten-year breakeven yields are at exactly the same level as they were when the RBA commenced the easing cycle in early 2025., Five-year, five-year forward breakeven yields are just 2.17%, well below the 2.4% at the start of the easing cycle, and ten-year, ten-year forward breakeven yields declined by 30bps over the year.

All of these measures are well below the mid-point of the RBA’s target band and are trending lower as time progresses.

Consumer inflation expectations have unsurprisingly followed published CPI inflation higher through 2025, and the RBA has chosen to highlight a very modest rise in inflation swaps, despite the RBA previously describing inflation swaps as ‘thinly traded and episodic’ as evidence of a rise in expectations.

Nevertheless, often the best measure of inflation expectations, especially in the nearer term, comes from surveys of firm output and retail pricing intentions. On this measure, Australian firms are indicating that inflationary pressures are stable if not moderating.

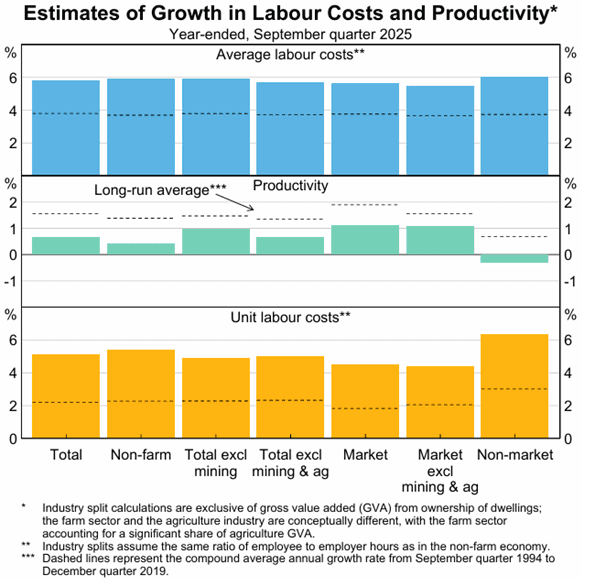

5. Productivity is headed into a sweet spot, not stagnation

The most concerning assumption that the RBA is making in its projection is the judgement that Australia’s productivity growth will not rise above current rates of growth over the next two years.

Chart 7. Productivity (ex-mining) is not near longer run trends

Source: ABS, RBA.

The chart above highlights the RBA’s breakdown of productivity. Note that the point we have been making consistently over recent years is that productivity ex-mining is not much below longer run trends, and the majority of the remainder of the gap is poor productivity growth recorded in the non-market sector. Some of this is mismeasurement of the health care sector’s productivity which we believe would add 0.5% to total economy productivity growth if it was measured correctly.

Nevertheless, even if the health care sector productivity data is unadjusted, the rotation of contributions of demand growth from the public sector to the private sector will continue to see some pick-up in productivity growth over coming quarters. With wage growth running at 3.7% (yoy), and seemingly in a trend slowdown given the near absence of full-time employment growth, then productivity around 1% is entirely consistent with inflation returning to the mid-point of the target band.

The Statement of Monetary Policy only provided fleeting references to AI, however the RBA seems to see AI as more a threat of boosting investment demand and input costs during the construction phase of data centres, rather than as a tool to enhance productivity. Indeed, the RBA continues to contrast itself from other central banks such as the Bank of Canada which regards increased investment spending as a force that increases the supply capacity of the economy rather than providing an inflation threat.

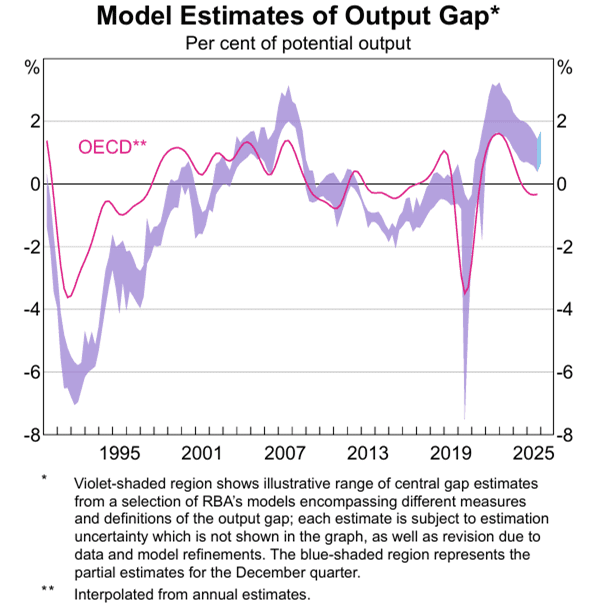

The real-world implication of holding a constant low productivity growth assumption into a cyclical improvement in demand is that it artificially lowers estimates of the supply side potential of the economy. The result is the RBA shows a range of estimates for the output gap that frankly look implausible.

Chart 8. The RBA’s very high estimate of Australia Output Gap

Source: ABS, OECD, RBA.

Most well-worn statistical approaches to estimating output gaps are merely fancy de-trending techniques and all the ones that we use show Australia with a negative output gap of around -0.5% of GDP at present, closer to the path shown by the OECD’s own estimate for Australia.

Indeed, relative to our G7 peers, we estimate Australia’s output gap is presently second only to Canada. Given most of the G7 are either actively considering further interest rate reductions or are on an extended pause in policy, the RBA’s dystopian view on Australia’s productivity potentially is the gravest misjudgement that it is making today.

The RBA Governor says she doesn’t know whether we are in a new rate tightening cycle or whether yesterday’s hike was just “an adjustment”. One thing we have learnt from the history of Australian monetary policy is that attempts to “fine-tune” an economy with monetary policy not only prove illusive but can also prove counterproductive.

In our view, the RBA is making too much of a small overshoot in trimmed mean inflation and could well be misinterpreting the causal factors behind the inflation pressures. In the process, it could be making the fatal error of setting Australia on a different interest rate journey relative to its peers.

This may unleash a further surge in the Australian dollar that ultimately smothers the nascent economic recovery that Australia was only just starting to enjoy. The RBA’s overly conservative views on Australia’s growth potential is suddenly a problem for all of us.

0 Comments